A conversation between Margaret Lee, Artist and Gallerist, and Martin Eisenberg

ME: Margaret, I consider this to be a “Post Cindy” show of photography. You’ve worked a long time as an assistant to Cindy Sherman, and you’re also an artist and gallery owner along with your husband, Oliver, of 47 Canal. How has Cindy influenced your practice and do you feel her influence in the work of Elle Pérez or Michele Abeles, two of the artists who you show?

ML: I would start by acknowledging Cindy and other artists of her generation for working to have photography be recognized outside of medium specificity. In breaking down the boundaries of artist vs. photographer, she and others paved the way for artists to continue pushing to make the medium more fluid, while broadening the audience. In moving away from the traditional values and rules of photography, artists like myself and Michele Abeles were freed from trying to achieve technical excellence only and to focus on the tensions between image vs. object in an increasingly digital landscape. Elle on the other hand, has embraced and excelled in the more technical aspects of photography and does so without losing the intimacy of their subjects. Though Cindy is known for only photographing herself, she is a master of emoting and thus creates portraits full of humanity, which Elle achieves while photographing others. There is a very special relationship between the person behind the camera and the person in front of the camera. It might seem as though the portrait exists to tell the story of the sitter but there is a lot that can be gleaned about the photographer through their gaze.

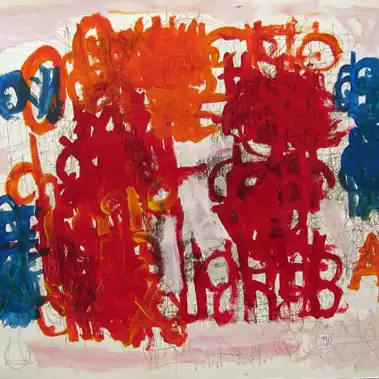

ME: You have two pieces in the show. I love both of them—very colorful, whimsical, and humorous. Tell us about your working process and how this series came about.

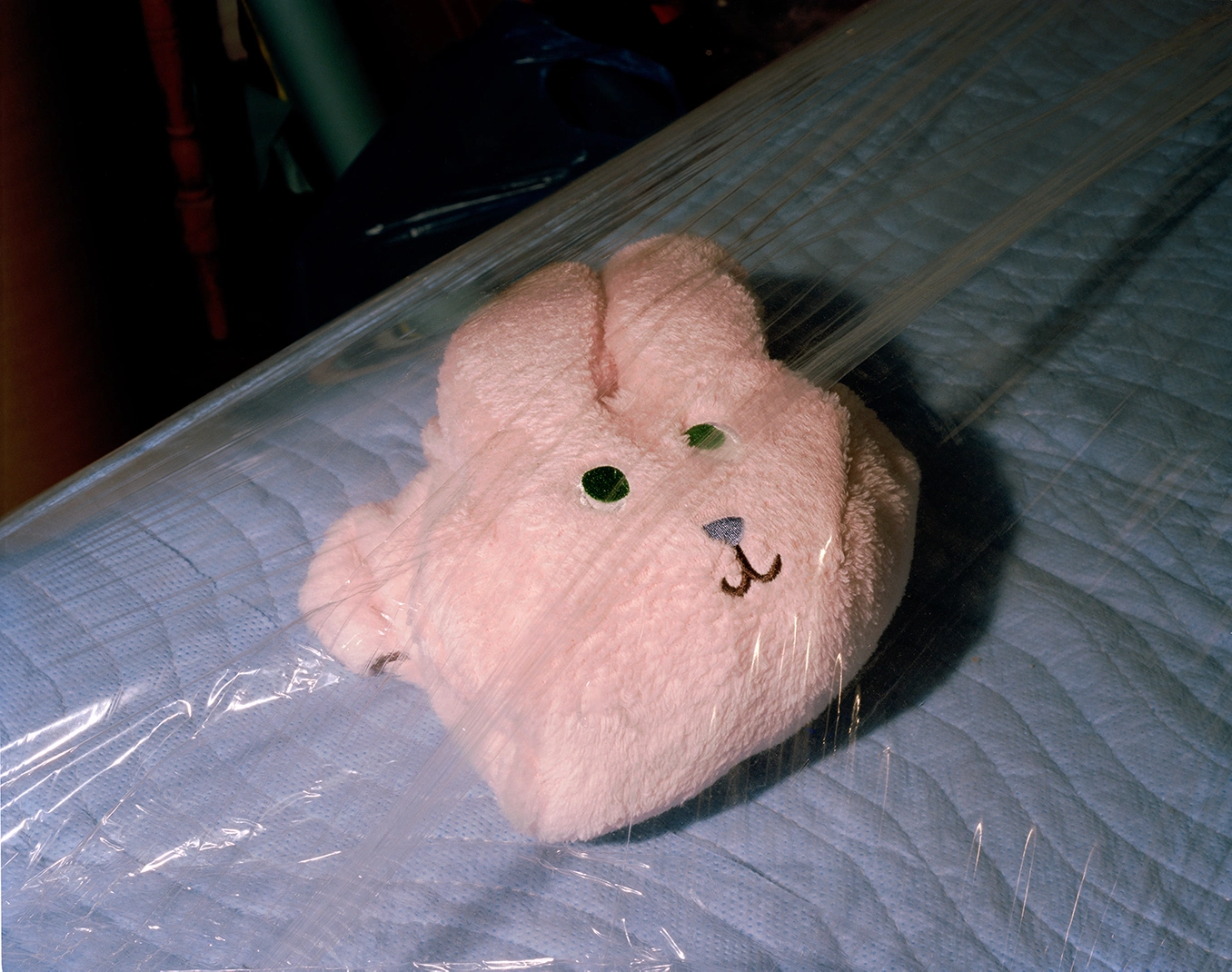

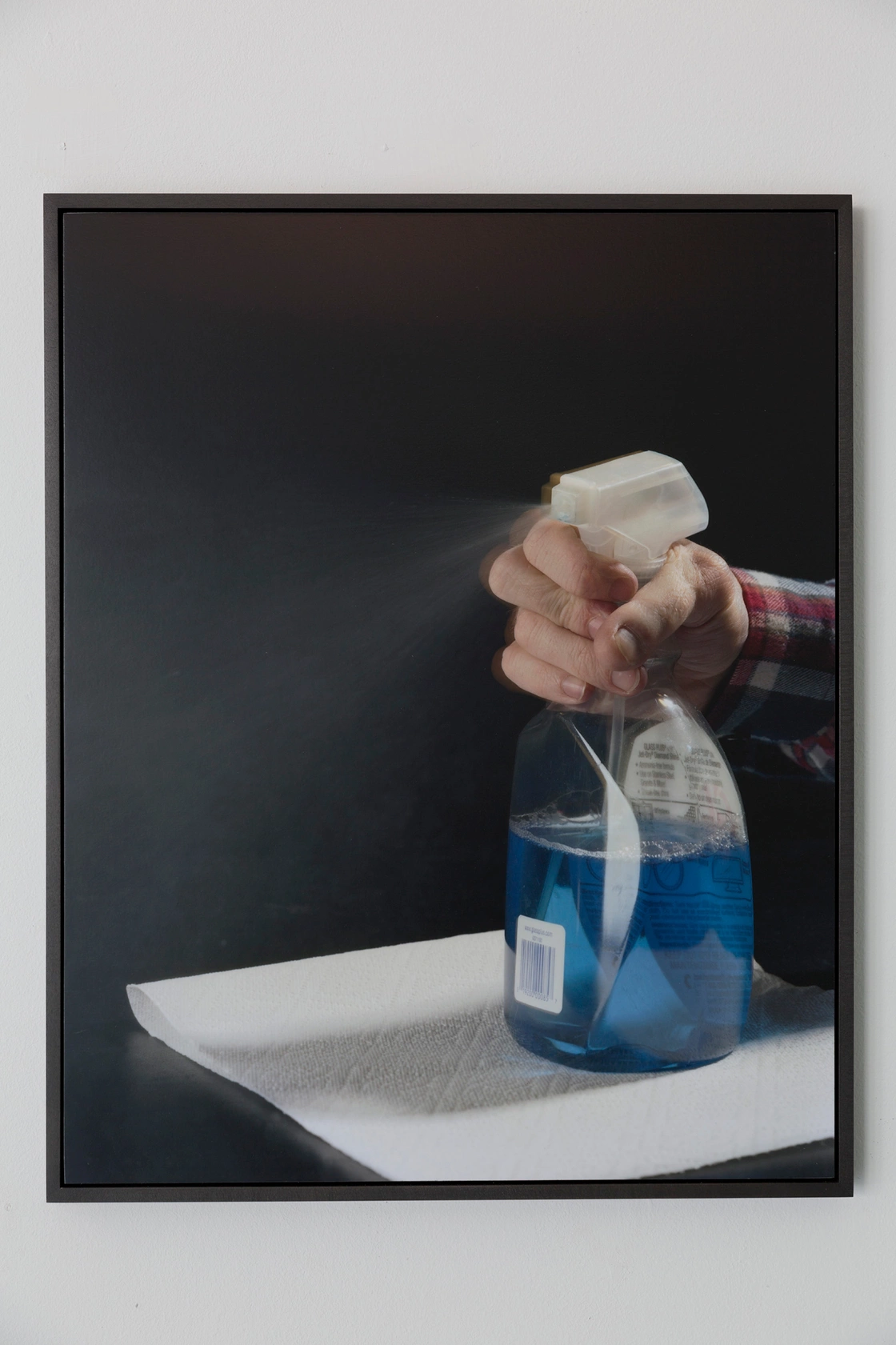

ML: Those small photos were made right before or in the early stages of my transition from running an artist’s run space to a gallery. The whimsy and humor are really important since both are collaborations with artists we represent at 47 Canal and the intention behind the collaborations was to remind ourselves why we were going ahead with the gallery project, which was to prioritize meaningful and playful exchanges. I was nervous that becoming a dealer would change the nature of my relationships and hoped this photo series would help me and my artists remember our shared values and our non-hierarchical conversations. I would invite an artist into my studio and allow them to lead the process while I facilitated set-up, camera, lights etc. It was an exercise in helping an artist actualize their vision on a small scale. It is an on-going series that I’ve tried to keep up with artists as they enter our program, as a way of building trust and deepening our understanding of each other.

ME: I see a relationship in your works with those of Elad Lasry and Saul Fletcher. All are small in scale and all are staged and then photographed. Do you feel the connection with these works or any others in the show?

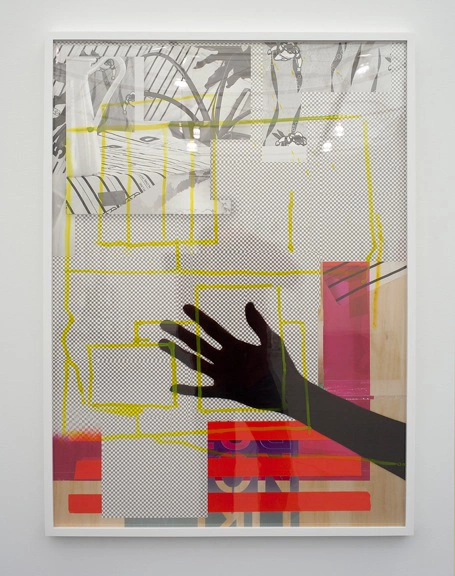

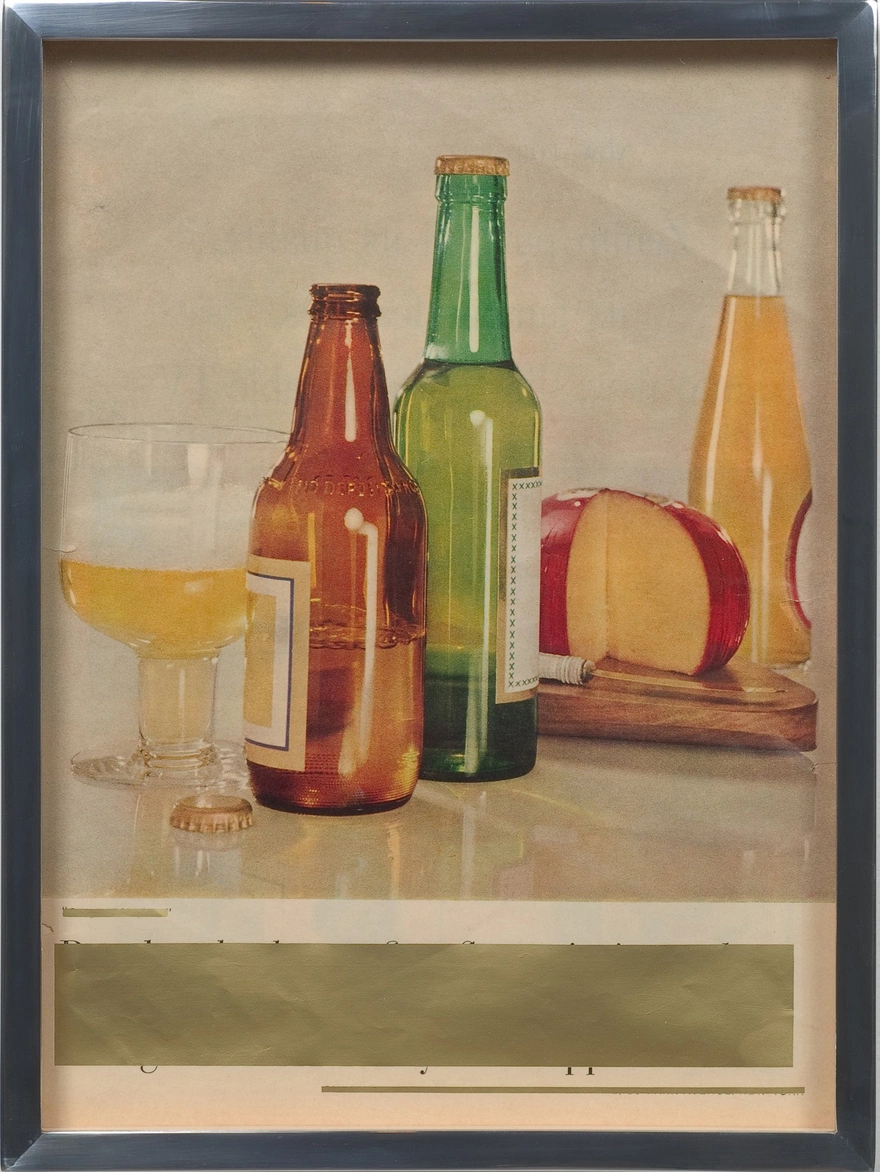

ML: I’m really attracted to work where inanimate objects take on life and emotion within an intimate scale. It’s not narrative that I am looking for but something more immaterial, a certain feeling that cuts through logic and connects us to deeper parts of ourselves and our desires that may still remain unknown. In looking at Elad Lassry’s work over the years, I’ve felt his works leave me feeling both elated and manipulated. This tension interests me. I’ve felt this way about Roe Etheridge’s work as well and am intrigued by these practices as I’m left questioning myself for being so easily attracted to their visual language as it relates to consumerism and advertising. Saul Fletcher’s work I am not familiar with but my initial reaction is that I am looking at something authentic, creativity without boundaries. It’s surprising to me that a work like Untitled #155 (snakes) is only 6.25 x 7 inches because the image itself is so grand and obviously human-scale. To capture that particular moment in “snapshot” scale perhaps makes me like it more. But to return to my love of photos of inanimate objects, Bad Situation 5, Lucas Blalock, might be my favorite work in this show. I’m not sure I have words for how the work makes me feel and this is how I know I like it so much. I’ve always felt somewhat reassured by your “eye” and how you go about collecting works. There is an ease and flow and nothing feels belabored or overthought. Do you feel that your connection to music, specifically jazz, has something to do with how you see and understand art?

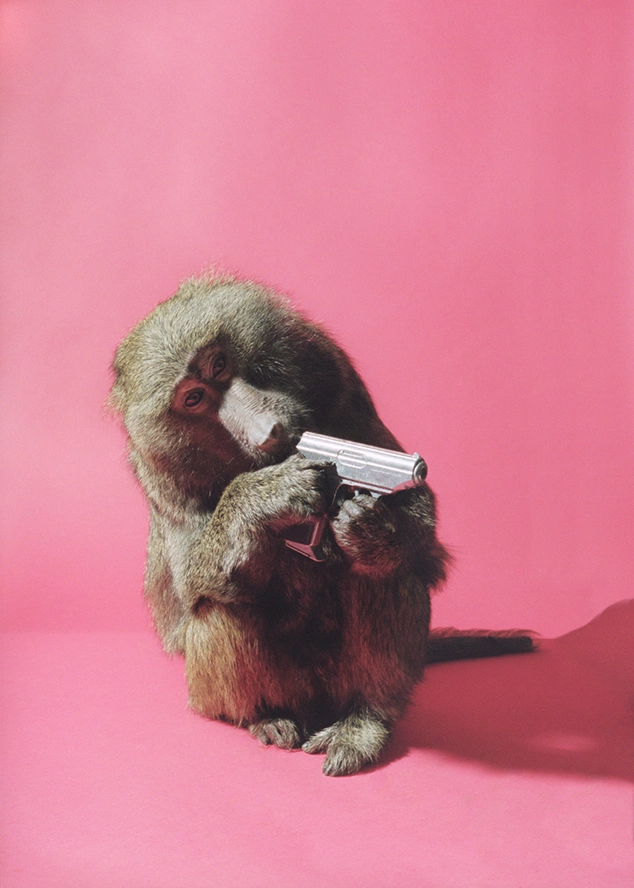

ME: Yes, jazz opened up my eyes in so many ways. After spending many years on a steady diet of rock music, I entered a new world in terms of sophistication, quality and integrity. It was so easy to see the difference and I worked hard researching the history and learning about different styles and genres within the field. Same goes with art. There is so much out there and you need to learn how to sniff out the imposters and to find quality. That is done through dialogue with institutions and by pounding the pavement and discovering the new. So much great music is being played in far off basement clubs around town and getting in there is not easy without guidance, not to mention the fact that newer forms of music take a while to get used to. You must develop an ear for it. Once you have a good set of ears it’s much easier to develop a good set of eyes. You are a trained musician so it’s easy for you to understand. When we hung the show I had the Heji Shin photo of the primate holding a handgun as the lead piece. It hit you when you first entered the building. Many members of the faculty objected to seeing this image in a school. They felt that it was a reminder of school shootings. We decided to move it to the very back of the show and replaced it with the Rachel Harrison. Interesting what happens when an artwork is taken out of the white cube of a gallery and shown in a different setting such as the Riverview School. It also makes you realize how powerful art is and the kind of emotions that it can bring out, something that people like us who surround ourselves within the art world can lose sight of. Your thoughts?

ML: I’ve spent the last couple of years re-examining my understanding of Art and why I work to create spaces for it to thrive. When I first started, the audience for my work and the work of the artists we show at the gallery was quite small. As we grew the audience, I realized the responsibility that comes with an expanded conversation and part of this was recognizing contextual shifts and taking the time to listen while protecting space for art to communicate freely. There is no one right way that applies across the board and because Art does communicate at times with such power and force, I think it is vital to seek feedback from a multitude of sources before exhibiting work in public spaces. We can’t always get it right, but this should not stand in the way of working with others to deepen our understanding because when it comes down to it, Art is meant to spark our imaginations and has the capacity to contribute to a more empathic world. It is listening and learning that allows us to, as you say sniff out imposters and find quality, and it is also what helps us to evolve so that we can continue to see with clarity so that we can continue to discover the new. You’ve been collecting for a long time. Do you often look back or reflect upon the process over the years and see how things have shifted?

ME: I reflect back on the times constantly whenever I stare at my collection, which is every waking hour when I’m at home. Each object is a reminder of the time in my life when I purchased it. From the earliest days of my marriage all the way up to last week. That being said, my method of collecting remains consistent. Always searching for the new and always trying to find works that will enhance and add depth to what we’ve built. The current show at Riverview features some terrific young artists that I’m excited about. Elle Pérez and Tomashi Jackson, to name two, fit right into our mission: bold political thinkers who express their beliefs in a compelling way much like Sharon Lockhart and Rachel Harrison, who we’ve been collecting from our earliest days. Heji Shin, who we mentioned earlier, reminds me of Roe Etheridge who we’ve been collecting forever. Both are fashion photographers who take off and spin the art form in different directions. The more things change the more they remain the same. Perhaps that’s a good place to end this. Thanks for taking the time. I look forward to walking the show with you.