Text from Amie Scally, White Columns

In a former auto body shop located in Oakland, California, a community of mentally, physically, and developmentally disabled artists gather on a daily basis to create and develop truly visionary bodies of art. This unique venue is home to Creative Growth Art Center, a non-profit visual arts space that was founded in the early 1970s by an artist and psychiatrist. The duo were frustrated by the limitations of traditional art-therapies and sought to find an alternative that would effectively nurture the creative process and improve the well-being of adult artists with disabilities through artistic expression. Creative Growth, comprised of a studio art program/workshop and a gallery, provides material support and encouragement to over 150 self-taught artists working in a variety of media, including painting, drawing, woodworking, and ceramics. The organization is “dedicated to the idea that people with disabilities can gain strength, enjoyment and fulfillment through the visual arts.” The outcome of fulfilling this mission over the past 36 years is remarkable – the creative impulses of thousands of artists with special needs have been fostered and promoted in a serious context. James Trainor, writing in Frieze Magazine, astutely observed: “Creative Growth isn’t a hospital, a clinic … or even a school in the strictest sense. No formal instruction is given, and there are no theoretical programs about how to educate the autistic or schizophrenic. What it is, is an experiment, now entering its fourth decade, rooted in distinctly northern California ideas about grassroots involvement, collective creativity and social change, about giving disenfranchised people the tools, space and support to express themselves.”

The artists have exhibited their work at Creative Growth’s gallery as well as galleries and museums around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and San Francisco, the Palais de Tokyo, Paris, and White Columns, New York, and are featured in a multitude of prestigious private and museum collections.

Spirit in the Dark: Art from Creative Growth features the work of David Albertsen, Dwight Mackintosh (1906 – 1999), Dan Miller, Aurie Ramirez, William Scott and William Tyler. The work on view demonstrates some of the range, depth, and complexity of the art made at the Center whilst revealing the artists’ respective intuitive sensibilities, and sophisticated visual language. The aptly chosen title of the exhibition, “Spirit in the Dark” is taken from a song recorded by Aretha Franklin and Ray Charles in 1971. It is a poetic metaphor for the process which takes place at Creative Growth. In many cases the individual’s exceptional talent has lain dormant for years or gone completely unrecognized, even in some instances for a majority of their life. By providing support and encouragement, this program not only allows these artists to finally realize and express their innate gift for art-making but also brings their extraordinary work into the world.

David Albertsen, a Mexican-American artist in his late twenties, works primarily with pastel on paper. His whimsical almost psychedelic-like drawings portray his instinctive sense of color and composition. The vibrancy of the color, emphasis on symmetrical patterning and a decorative quality evoke the traditions of Mexican Folk Art. Albertsen’s work has been exhibited at White Columns, New York and the NADA Art Fair in Miami.

Dwight Mackintosh (1906–1999) Mackintosh, identified by the art historian John McGregor as a great American “Outsider” artist, began his art career at Creative Growth after spending over 55 years in institutions. During his time there, he developed a large body of work including drawings, paintings, prints and ceramics. Mackintosh primarily creates linear ‘x-ray’ like drawings of male figures often combined with repetitive mostly unintelligible text drawn in a fluid cursive style, suggesting a means of communication through art-making. Mackintosh’s work has been exhibited internationally and most recently at ABCD Collection, Paris and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.

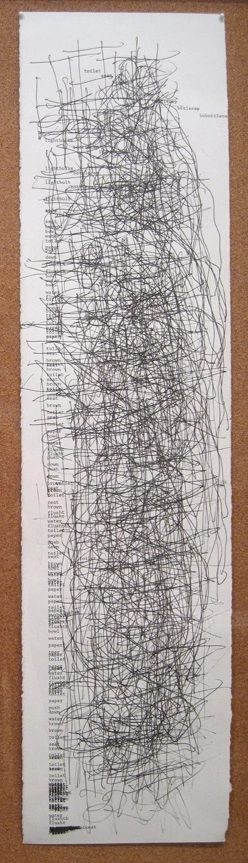

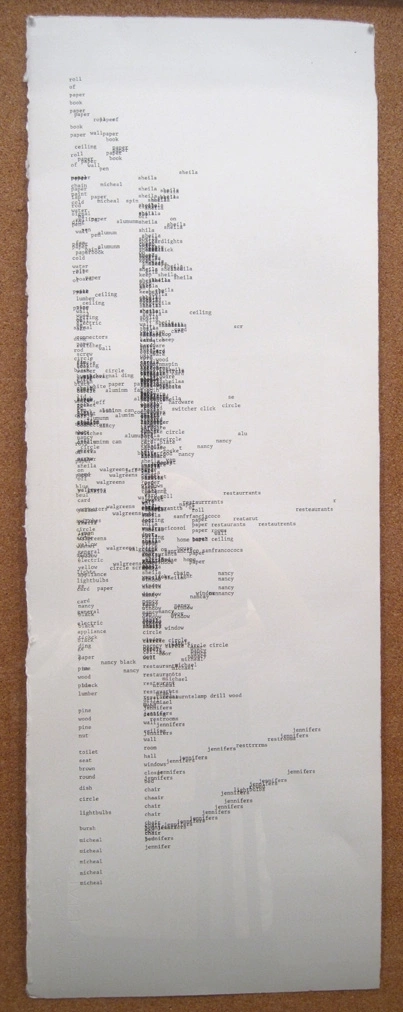

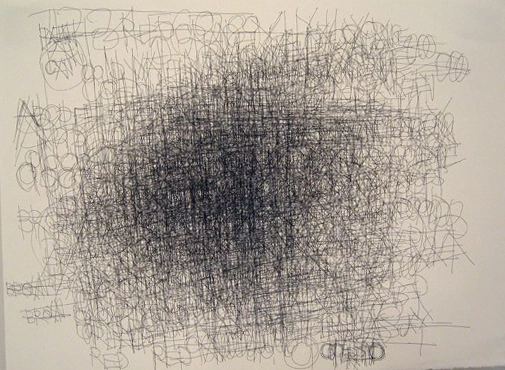

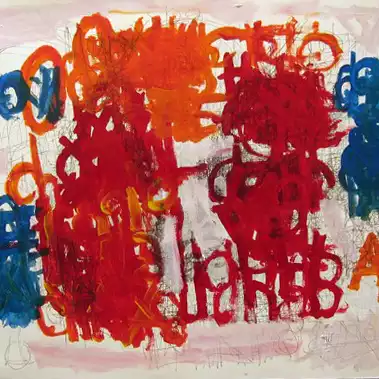

Dan Miller (b.1961) has few verbal skills, yet has created a body of work that uses language as its foundation. His ink on paper drawings feature overlaid accumulations of recurring words (certain objects like light bulbs, tools and electrical sockets, names of cities and types of food are favored), alphabets, and numbers, with the densely layered lettering ultimately rendering the text mostly illegible. The resultant all-over compositions juxtapose controlled and expressive styles, revealing Miller’s innate formal sensibility and reverberate with art historical traditions. The artist’s work has been most recently exhibited at Ricco/Maresca Gallery and Wallspace Gallery, New York and has been exhibited at White Columns, Gavin Brown’s enterprise, and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Miller’s work is held in the permanent collection of the MoMA.

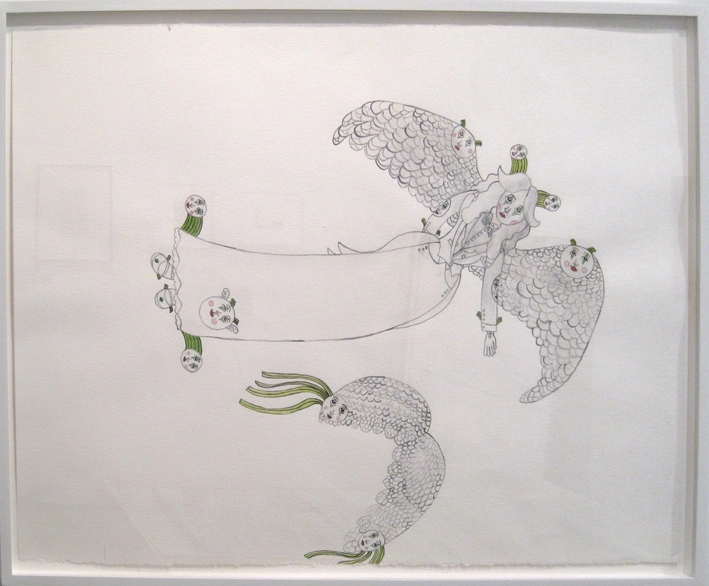

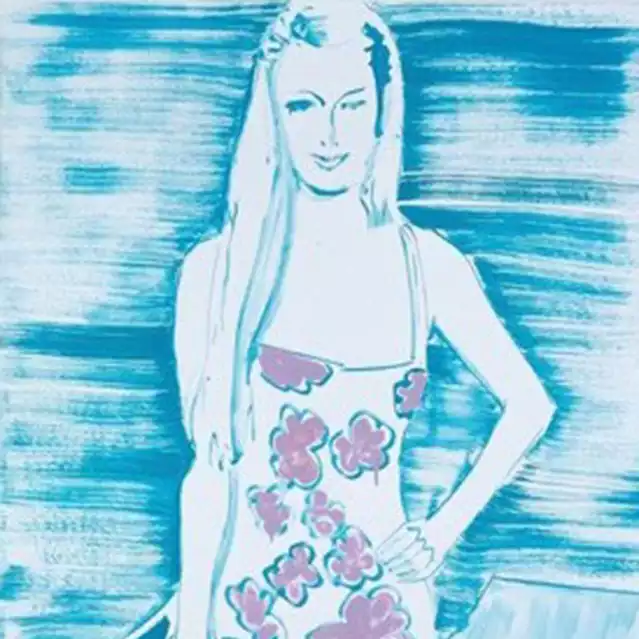

Aurie Ramirez (b. 1962) Over the past twenty years, Ramirez has developed a visionary body of work featuring mostly watercolor and ink drawings that, reminiscent of the work of self-taught artist Henry Darger, are populated by a recurring cast of characters and narratives. The artist, who does not communicate verbally, has a wide range of inspiration and interests – from the Addams Family, the rock band Kiss, Glam and Punk Rock to 18th century Victorian dandies and suburban California ‘modernist’-style interiors. Ramirez’s work has been exhibited in shows at White Columns and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York, Jack Hanley Gallery, Los Angeles, Midway Contemporary, Minneapolis, ABCD in Paris, Collection l’Art Brut, Lausanne, and Confort-Moderne, Poitiers, France.

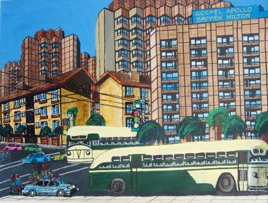

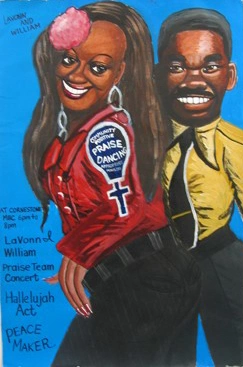

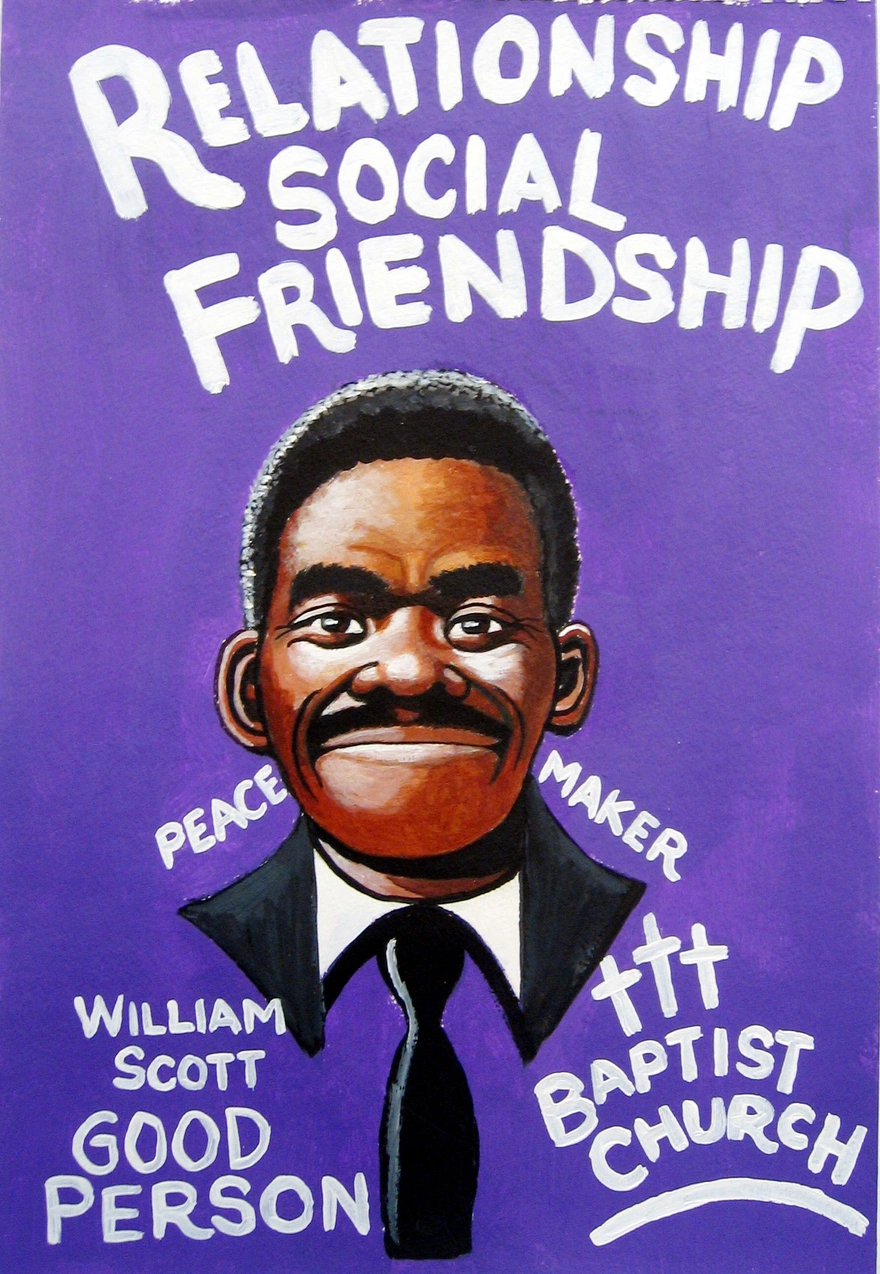

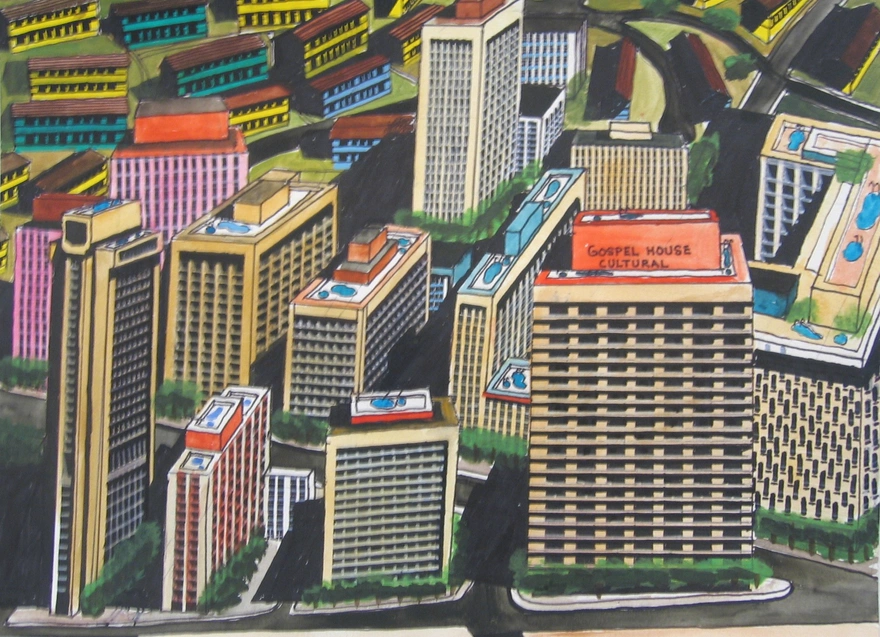

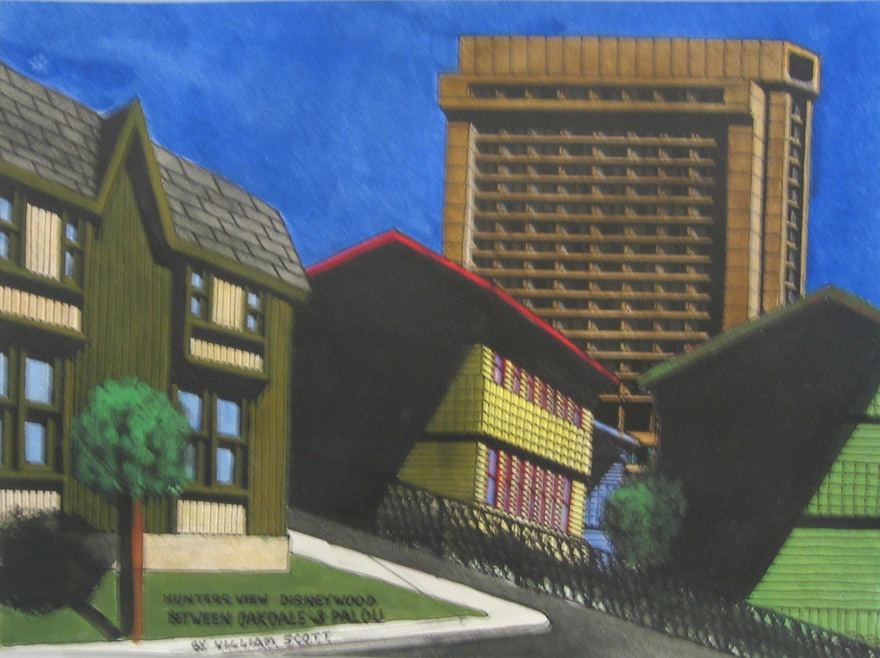

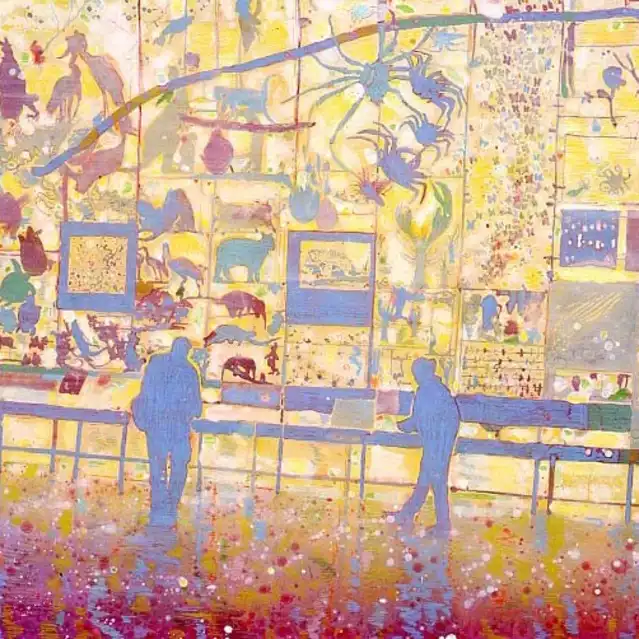

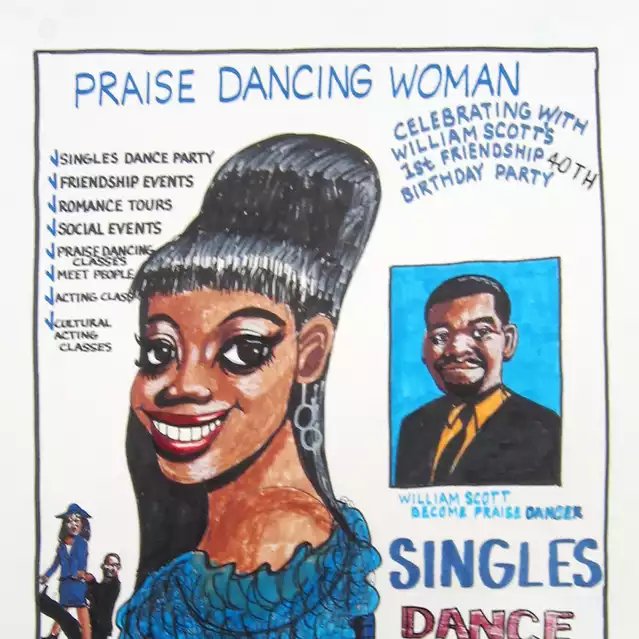

William Scott’s (b. 1964) highly detailed and richly imaginative practice is composed of two parts: portrait works, featuring Scott, friends, relatives, and invented characters involved in real and imagined episodic scenarios that are situated within his community of Hunters Point in San Francisco (most moving are those in which Scott envisions a life without his disability, i.e., as a basketball player, a policeman, etc.), and architectural renderings of an idealized imaginary version of San Francisco he calls “Praise Frisco.” Describing the impact of Scott’s work, Matthew Higgs, Director of White Columns, wrote “Whilst rooted in personal experience, William Scott’s work ultimately addresses universal questions of identity, community, faith, and the daily challenges we all face navigating reality.” Scott’s work has been exhibited at White Columns and Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York and in a solo museum exhibition (curated by Matthew Higgs) at the Palais de Tokyo, Paris.

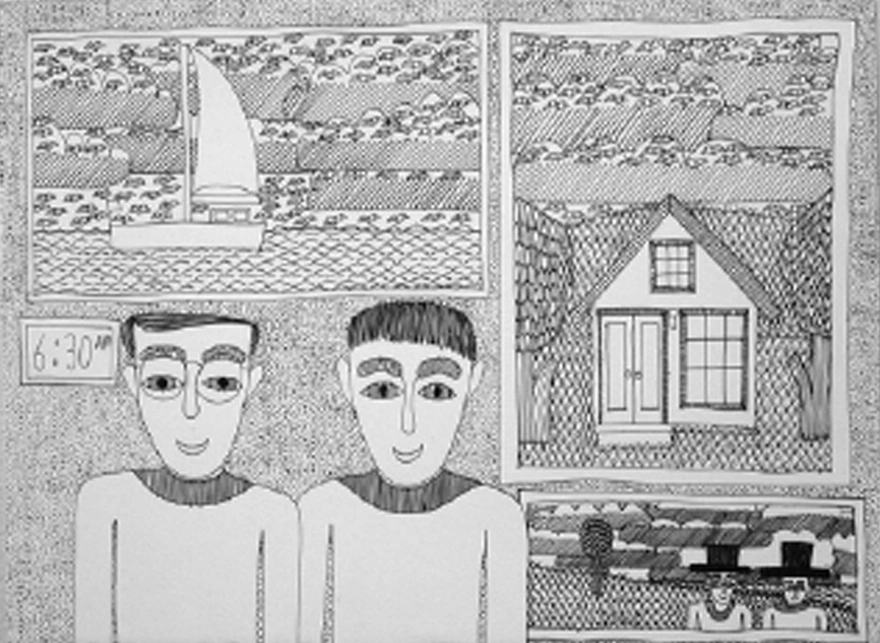

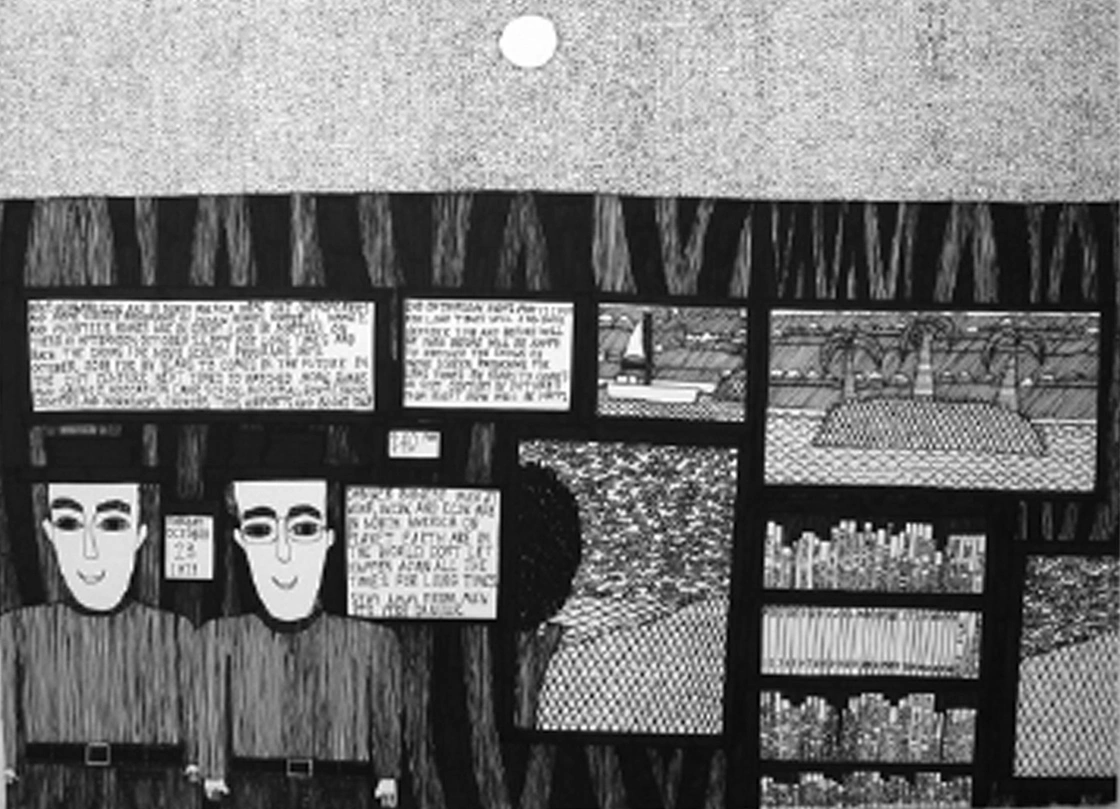

William Tyler’s (b. 1954) body of work is also composed of an ongoing invented narrative, in this case one that regularly features Tyler and his twin brother Richard. The artist, who makes a drawing a day, has created a fictive parallel reality he calls “Greatland.” The drawings depict the ongoing adventures of the brothers in this utopian world along with descriptive texts, the exterior and interior of the houses that occupy Greatland, hospital interiors, landscapes, restaurants, magic shows etc. The complexity of the patterning and composition of these extraordinary ink on paper drawings demonstrates Tyler’s exceptional skill and acute perception of the world. Tyler’s work has been featured at the NADA art fair, Miami and at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, New York.